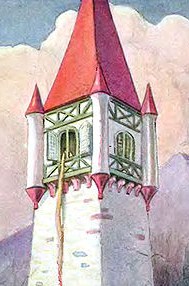

Once upon a time, there was a princess in a tower….

Okay, what happens next? Realistically, we have a few options:

- The princess is rescued, ideally by a handsome prince.

- The princess escapes entirely under her own steam, thank you very much.

- The princess stays there. It’s her home, and she’s severely agoraphobic.

Each one is variously subversive. But there’s one thing that’s almost certain—we will not have a story in which a princess lives in a tower because it’s convenient for the shops. It doesn’t matter how post-modern the rest of her tale is—the all-powerful fairytale demands at least a reference.

And I, for one, wouldn’t have it any other way.

We are steeped in stories. One of the best ways to calm a small child is to read them a story, even though they might understand very few of the words. There’s something about the rhythm of the words and the progress of the plot that makes them comfortable. And it doesn’t change as we grow older. Stories shape our thoughts. Often, we only really grasp a piece of news when it is structured into a narrative. Some evolutionary biologists believe that homo sapiens became the species it is today because prehistoric man learned to tell each other stories. It developed their ability to recognise situations that they had no firsthand experience of, and subsequently helped them extrapolate what would be the right decision.

And the oldest stories are always fantasy. These are the legends of the birth of the world; the tales of a crocodile that swallows the sun, is cut apart by a hero with time on his hands, and the universe comes tumbling out like some unholy piñata. These are the stories of demonic men who take a hundred wives and kill them all, until defeated by a plucky orphan with three spoons, a talking wombat, and a sense of entitlement.

These stories don’t have to make sense (really, Red Riding Hood’s granny looked like a wolf in a mob cap, did she? Well, I pity her grandfather), and their original meaning may well have vanished (you do not want to know about the original version of Sleeping Beauty. Really.), but still, they remain iconic, and continue to turn up in a million different guises.

In many forms of fiction, these structures and tropes need to be hidden. A classic Bildungsroman, a novel following the life story of single person as they mature, will certainly mirror one of the ancient plots–the protagonist going from rags to riches, say, or perhaps a tragic fall and rebirth. A monster story is still a monster story when the villain is a brutal and gritty drug dealer, and the lonely city streets, walked by modern police, owe much to the dark forests of old. But these often unconscious references will be buried in incidental detail, for fear that it would make the fiction derivative, or unoriginal.

But unreal fiction can revel in these structures. In fact, for me, one of the joys of fantastic fiction is spotting those little homages to those ancient tales.

Terry Pratchett, in particular, is famous for his love of subverting these influences. Everyone in his later Discworld books seems to be at least partially aware of being in a story. Traditional vampires reminisce with angry mobs, whilst modern, reformist, vampires sign on to the black-ribbon pledge never to drink blood again. A governess who is descended from the Grim Reaper (don’t ask) deals with childish fears of bogeymen by dragging the actual monsters from under the bed and beating them senseless with a poker. And two incompetent guardsmen escape from certain doom because million-to-one chances “happen nine times out of ten”… but only exactly million-to-one chances. When they accidentally attempt something which is more like a 963,000-to-one chance, they aren’t so fortunate.

But surely, there is a danger here. There are so many old legends, so many iconic tales, all of them blissfully fantastic—how can modern fantasy and science fiction ever be truly original? How can it find its own identity in the face of so much history?

Once more, Terry Pratchett comes to the rescue.

One of his novels, Witches Abroad, revolves around the protagonists’ attempt to prevent a fairy tale ending from coming to pass. Towards the end of this novel, there is a very telling little exchange. The heroine and the villain (to say anymore would spoil it), have woken up in a dreamscape walled with mirrors. They are confronted by their own image, multiplied to infinity. Death, the Grim Reaper (yes, he turns up a lot in Discworld), says that they can escape if they find the real version of themselves. The villain runs off, frantically searching for the correct reflection. The heroine takes one long moment to think, and then points to herself.

“This one,” she says.

And that is the most important thing to remember. It doesn’t matter how many reflections of these ancient tales appear, or how much influence they have—there is always room for another story, and the most important one at any time is the story being told. These tales are endlessly varied, and endlessly new. It just takes that old, familiar parallel to make us look at the new story in a fresh way.

And this doesn’t need to stop when you put down the book. A good fantasy tale or science fiction exploration can change the way you look at the world around you. Looked at through the eyes of a fan of unreal fiction, the greatest wonders of all can be found in the places where no dragon would dare to tread—our own world.

But that’s another story.

Read the entire Thoughts on the Unreal series.

David Whitley is the author of The Midnight Charter and its sequel, The Children of the Lost, out now in the U.S. He lives in Britain, where naturally we all have castles of our own. No exceptions. Those moats cause some problems with commuting, but we manage somehow….